|

|

Al-Mizan Allamah as-Sayyid Muhammad Husayn at-Tabataba'i Chapter 7

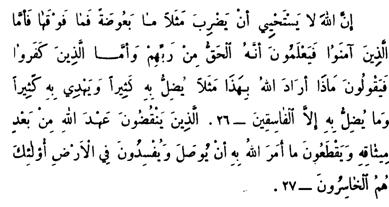

Surely All‚h is not ashamed to set forth any parable - (that of) a gnat or any thing above that; then as for those who believe, they know that it is the truth from their Lord, and as for those who disbelieve, they say: "What is it that All‚h means by this parable?" He causes many to err by it and many He leads aright by it, but He does not cause to err by it (any) except the transgressors (26), who break the covenant of All‚h after its confirmation and cut asunder what All‚h has ordered to be joined, and make mischief in the land; these it is that are the losers (27). * * * * * COMMENTARYQUR’ĀN: Surely All‚h is not ashamed. . . : Gnat or mosquito is one of the smallest animals perceptible by naked eyes. These two verses run parallel to verses 19 - 21 of ch. 13: Is then he who knows that what has been sent down to you from your Lord is the truth like unto him who is blind? Only those pos≠sessed of understanding shall bear in mind, those who fulfil the promise of All‚h and do not break the covenant, and those who join that which All‚h has bidden to be joined, and fear All‚h and fear the evil reckoning. The verse clearly shows that there is a straying, a blind≠ness, which afflicts the man as a result of his evil deeds; it is different from that initial straying and blindness which the man opts for by his own free will. Look at the sentence, "but He does not cause to err by it (any) except the transgressors". They transgressed first, and it was only then that All‚h made them go astray. Guidance and misguidance are two comprehensive words; they encompass every felicity and infelicity that comes from All‚h to His good and wicked servants respectively. As All‚h describes in the Qur’‚n, He makes His good servants live a happy life, strengthens them with the spirit of faith, bring them out of the darkness into the light, and gives them a light by which they walk among the people; He has taken them under His protection and guardianship, and there is no fear for them, nor shall they grieve; He is with them, answers them when they call on Him, and remembers them when they remember Him; and the angels come down to them with good news of eternal peace. Diametrically opposed to it is the condition of evil-doers. All‚h causes them to err, takes them out of the light into the darkness, sets a seal upon their hearts and hearings, and a cover≠ing over their eyes; He alters their faces turning them on their backs; places chains on their necks and these reach up to their chins, so they have their heads raised aloft, and makes a barrier before them and a barrier behind them, then He covers them over so that they cannot see; He appoints for them the Satans to become their associates, and they turn them away from the right path while they think that they are guided aright; those Satans make their misdeeds to seem good to them and they are their guardians; All‚h leads them on by steps from whence they perceive not; and yet He respites them, but His plan is firm; He makes a plan for them and leaves them alone in their rebellion, blindly wandering on. These are some examples of the conditions of the two groups. On deeper consideration, it appears that man, in this world, lives two lives: there is this life which may be seen and perceived by all, and there is another life hidden behind this one; that hidden life is either good or bad - depending on his faith and deeds. Man will become aware of that hidden life when the veil of secrecy will be removed after death. Then he will see himself in his true form. Further, it appears from the Qur’‚nic verses that man has had a spiritual life before the life of this world; and he shall have another life after this one. In other words, man has been given three lives - this life in this world is the second one, there was one preceding it and there will be another following. The con≠dition of the third life shall be determined by that of this second life - which, in its turn, is governed by the first one. Many exegetes have explained away the verses about the first life; they say that it is only a literary style, which presents imaginary pictures as real facts. And as for the verses concerning the life hereafter, they too are misrepresented as allegories and metaphors. But both types of verses are too clear in this meaning to allow such misinterpretations. We shall explain the verses about the first life under ch. 7. As for the life hereafter, many verses show that the same good or bad deeds which man commits in this life, shall be returned to him, as their own reward or punishment, on the day of requital. All‚h has mentioned this fact in many verses: . . . and do not make excuses today; you shall be recompensed only what you did (66:7); then every soul shall be paid back in full what it has earned, and they shall not be dealt with unjustly. (2:281); then be on guard against the fire of which men and stones are fuel (2:24); Then let him summon his council, We too would summon the tormentors (of the hell) (96:17-18); On the day that every soul shall find present what it has done of good and what it has done of evil . . . (3:30); . . . they eat nothing but fire into their bellies . . . (2:174); . . . surely they only swallow fire into their bellies . . . (4:10). There are many verses of the same import. Then there is the verse 50:22, which by itself is enough to convince one of this principle: Certainly you were heedless, of it, but now We have removed from you your veil, so your sight today is sharp. The words, "you were heedless of it", indicate that there was something present in this world, to which the guilty one has not paid any attention; "removed from you your veil" means that, but for that veil, he could have seen that reality even in this worldly life. What the man would see on the Day of Resurrection was present even in this earthly life; otherwise, it would not be logical to say that previously you were inattentive to it, or that it was hidden from your eyes, but now that the cover has been removed, you may see it clearly. There is no allegory or metaphor in these verses. Try to explain in plain Arabic the principle which we have mentioned just now. You will not find a more explicit way than the one used in these verses. Then, how can they be explained away as allegories? The divine talk here points at two realities:- First: Recompense: What a man will get in hereafter - reward or punishment, paradise or hell - shall be in recompense of the good or evil he would have done in this life. Second: Embodiment of the deeds: Many verses indicate that the good or evil deeds themselves turn into their own pleasant or unpleasant recompense. (Or, that the recompense is an insepar≠able concomitant of the deeds themselves.) It is hidden from our eyes in this life, but we shall see it clearly on the day of reckoning. These realities are not really two. But we had to explain it in this way to bring it nearer to the minds. The Qur’‚n too says that it uses similitudes to make people understand. QUR’ĀN: but He does not cause to err by it (any)

except the transgressors: "al–Fisq” ( You should never think that the adjectives used by All‚h in His book for His good servants (like "those who are near to All‚h", "the sincere ones", "the humble ones", "the good ones", "the purified ones" etc.) or for the evil ones (like "the unjust", "the transgressors", "the losers", "those who go as≠tray", etc.) are cheap epithets, or that they are used as literary embellishment. Each adjective has its own significance; each points to a particular stage in man's spiritual journey. Each has its own characteristics, and gives rise to its especial effects and consequences. On physical level, every age has its own char≠acteristics and powers, which cannot be found before or after that age; likewise, on spiritual plane, every attribute has its own special effects. AN ESSAY ON COMPULSION AND DELEGATIONThe sentence, "but He does not cause to err by it (any) except the transgressors", explains how All‚h manages the actions of His servants. Does He compel them to act in a pre-determined way? Or, has He delegated to them all powers in this respect? It is better to solve this knotty problem here and now, by the guidance of the Qur’‚n. All‚h says: Whatever is in the heavens and whatever is in the earth is All‚h's (2:284); His is the kingdom of the heavens and the earth (57:5); to Him belongs the kingdom, and to Him is due (all) praise (64:1). These and other similar verses prove that to All‚h belongs the whole universe; His ownership is unconditional and unlimited. A man owns a thing, let us say, a donkey; he may use it and take its advantage to a certain extent only. For ex≠ample, he may ride it or use it as a beast of burden; but he can≠not starve it to death, nor can he burn it alive. Why? Because his ownership is not absolute; society would condemn him if he were to commit such atrocities. His ownership allows him certain advantages only; and not every possible use. But when we say that All‚h is the Owner of the worlds, we mean absolute, real and unrestricted ownership. There is no owner except All‚h; the things own, or control, for themselves neither any harm nor any profit, neither life, death no resurrec≠tion. It is only All‚h who owns and controls every affair of every creature; He may do with them whatever He pleases; no one can ask Him why; He cannot be blamed or questioned for anything He does, because He is the absolute Owner. He has, of course, allowed some of His creatures to use some other things to a cer≠tain limits; but both the user and the used are His property; and the user cannot exceed the authorized limit. All‚h, as the absolute Owner, cannot be questioned about His dispositions; but others have to give account of how they exercised their authority. All‚h says: who is he that can intercede with Him but by His permis≠sion? (2:255); there is no intercessor except after His permission (10:3); . . . that if All‚h please He would certainly guide all the people? (13:31); And if All‚h please He would certainly make you a single nation, but He causes to err whom He pleases and guides whom He pleases . . . (16:93); And you do not please except that All‚h please (76:30); He cannot be questioned concerning what He does and they shall be questioned (21:23). All‚h disposes and manages His property in any way He pleases; no one can use any other thing except with His permission, because He is the real Owner and Sustainer of every thing. Now we come to the rules and laws which All‚h ordains for His creatures. He uses the same method which has been adopted by the human society - ordaining what is good and praising and rewarding its doers; forbidding what is bad and condemning and punishing its doers. For example, He says: If you give alms openly, it is well (2:271), . . . evil is a bad name after faith (49:11). Obviously, the laws ordained by All‚h look at the good of man, and aim at perfecting the human society. All‚h says: . . . answer (the call of) All‚h and His Apostle when he calls you to that which gives you life (8:24); that is better for you, if you know (61:11); Surely All‚h enjoins the doing of justice and the doing of good (to others) and the giving to kindred, and He forbids indecency and evil and rebellion (16:90); Surely All‚h does not enjoin indecency (7:28). There are many such verses; and they show that the principles which the laws are based upon are always the same - be it a divine commandment or a human legislation. What is good in itself and ensures the good of the society is allowed, enjoined and prescribed; and what is evil in itself and endangers the social structure is forbidden; man is praised and rewarded for doing the former, and blamed and punished for doing the later. Some of those principles are as follows:- People do whatever they do because of its underlying wisdom and good. Legislation of laws is no exception to this rule; the laws too are made because of their underlying good and benefit. They reward the law-abiding citizens and chastise, if they so wish, the law-breakers. The said recompense must be correlated to the action done - in its quantity and quality. Also, it is accepted that the enjoinment and prohibition can be addressed to him only who is not under any duress or compulsion who has got freedom of will and choice. The above-mentioned recompense too is related to such actions only which emanate from free will and choice. Of course, if someone, by his own action, puts himself in a tight corner, in a difficult position where he has to transgress a law, he may be justly punished for that trans≠gression, and his plea of helplessness will not be heeded at all. All‚h uses these same principles in His dealing with His creatures. He does not compel the man to obey or to disobey the divine commands. Had there been any compulsion, rewarding the obedient ones with the paradise and punishing the disobedient ones with the hell would have been absolutely wrong: the reward would have been an unprincipled venture, and the punishment an unmitigated oppression and injustice - and all of it is evil according to reason. Moreover, it would mean favouring one against the other without any justification, without any cause – and this too is a demerit according to reason. Furthermore, it would provide the aggrieved party with a valid argument against All‚h; but All‚h says: . . . so that people should not have an argument against All‚h after the (coming of) apostles (4:165); . . . that he who would perish might perish by clear proof, and he who would live might live by clear proof (8:42). The above discourse makes the following points clear:- First: Divine laws are not based on compulsion. These rules have been made for the good of man in this life and the hereafter. And they have been prescribed for him because he has freedom of will, he may obey the rule if he so wishes, and may disobey if he so chooses. He will be fully recompensed for what≠ever good or bad he does by his free will. Second: There are things and actions which are not in conformity with the divine sanctity, yet the Qur’‚n attributes them to All‚h, like misleading, deceiving, scheming against some≠one, leaving him wandering on in his rebellion, letting the Satan overpower the man and become his associate. All these actions are related to various kinds of misleading and misguidance. But All‚h is above all defects and demerits, and, therefore, these words when attributed to Him, should convey a meaning in keeping with His sacred name. Initial misleading, even in the sense of making inattentive and forgetful, cannot be ascribed to All‚h. What the above-mentioned expressions actually mean is this: When someone by his own free will, opts to go astray, chooses the wrong path and commits sins, then All‚h leaves him in that straying, and, thus, increases his error - it is done as a punishment of his wrong choice. All‚h says: He causes many to err by it and many He leads aright, by it, but He does not cause to err by it (any) except the transgressors (2:26) . . . . when they turned aside, All‚h made their hearts turn aside (61:5). Thus does All‚h cause him to err who is extravagant, a doubter (40:34). Third: The divine decree does not cover the actions of the man inasmuch as they are attributed to him - they are done by the doer, although not created by him. We shall further explain it later. Fourth: Now that it has been seen that the divine law is not based on compulsion, it should be clearly understood that it is not based on delegation of power either. How can a "master" issue an authoritative command if he has delegated all his powers to the servant. In other words, this theory of delegation ne≠gates the comprehensive ownership of All‚h vis-ŗ-vis many of His possessions.

TRADITIONSA great number of traditions (narrated from the Im‚ms of Ahlu 'l-bayt - a.s.) says: "There is neither compulsion nor delegation (of power), but (there is) a position between these two (extremes)." It is reported in ‘UyŻnu ’1-akhb‚r, through several chains: When the Leader of the faithful, ‘AlÓ ibn AbÓ T‚lib (a.s.) returned from SiffÓn, an old man (who has participated in that battle) stood up and said: "O Leader of the faithful! Tell us about this journey of ours, was it by All‚h's decree and measure?" The Leader of the faithful said: "Yes, O Shaykh! By All‚h you did not ascend any elevation, nor did you descend to any valley but by a decree of All‚h and by His measure." The old man, there≠upon said: "I leave to All‚h all my troubles (of this journey), O Leader of the faithful!" (‘AlÓ - a.s.) replied: "Have patience, O Shaykh! Perhaps you take it to mean a firm decree and a com≠pulsory measure! If it were so, then there would be no justifica≠tion of reward or punishment, no sense of command, prohibition or admonition, no meaning of promise or threat; there would not be any blame on an evil-doer nor any praise for a good-doer. Nay, the good-doer would have been rather more deserving of blame than the evil-doer, and the evil-doer rather more worthy of grace than the good-doer. (Beware!) this is the belief of the idol-worshippers and the enemies of the Beneficent God (who are) the Qadariyyah of this ummah and its MajŻs. O Shaykh! Verily All‚h ordained (the sharÓ‘ah) giving freedom of will (to men) and prohibited (evil) to keep us on guard; and He gave plentiful (reward) on meagre (deeds); and He was not disobeyed by being overpowered, nor was He obeyed by compulsion; and He did not create the heavens and the earth and what is between them in vain; that is the opinion of those who disbelieve on account of the fire." The author says: The topics of the speech of All‚h and His decree and measure were among the earliest about which the Muslims differed among themselves. This second dispute may be described as follows: The eternal divine will govern every thing in the universe. These things are transient in their quiddity; but when they do exist, they do so because the will of All‚h decreed their existence - and in this way their existence becomes essential - otherwise, the divine decree would be meaningless. Conversely, when a thing does not exist, it is because All‚h did not decree its existence - and in this way its existence becomes impossible - otherwise, the divine will would be meaningless. In short, whatever exists, exists because All‚h has decreed its existence, - thus turning it into an essential being. This principle applies everywhere. But the difficulty arises when it comes to such a human action that issues from our own will and choice. We know that we can do it if we so desire, and can ignore it if we so wish. Their doing and not doing is equally possible to us. The balance is tipped in favour of either side by our own will and choice. Our actions are based on our choice, and our will brings them into existence. The difficulty that arises at this point is this: We have earlier seen that nothing comes into being without the will and decree of All‚h, which turns the thing into an essential being - if so, then how can any action of ours be termed as "possible" one? It must exist because the divine will has decreed it! Moreover, how can our will affect it in any way when it is governed by the will of All‚h? Also, in this background, it cannot be said that man had power to do a certain work before he did it. And, because he did not have that power, All‚h could not give him any order or command for or against that work. Going a step further, if All‚h gave him an order and he did not comply, it would mean that All‚h Himself had not wanted that thing to happen; so it was impossible for it to happen. Then the question would arise: How could All‚h order him to perform an impossible task? Conversely, if someone complied with that order, it was because All‚h Himself wanted it to happen. Then why should the man be rewarded without any valid reason? By the same reasoning, a sinner should not be punished, as it would be against justice, a naked oppression. One may go on enumerating the difficulties arising out of this subject. A large number of Muslims felt obliged to admit, and believe in, all these absurdities. They said that: Man does not have power to do a work before the time comes to do it. The reason has nothing to do with the merit or demerit of any action. Whatever All‚h does becomes good; and whatever He forbids becomes evil. Accordingly, All‚h may choose an action without any justification; He may give reward without any cause; He may ordain laws beyond the capacity of the doer or agent; He may inflict punishment on a disobedient servant even though the said disobedience and transgression was not of his doing. It appears that the old man, who had asked the question, thought that the belief in the divine will and decree meant that there was no merit or demerit in any action and that man had no right of any reward (or punishment). Naturally he was dis≠appointed when he heard that the journey was by the decree of All‚h; that is why he said: "I leave to All‚h all my troubles." What he meant was this: My journey to SiffÓn and back and my fighting in the way of All‚h had no benefit for me as it was governed and done by the will of All‚h; my share in all this venture was only the trouble and the inconvenience which I underwent. Therefore, I shall leave it to All‚h to balance my account, as it was He Who put me through all these troubles. The Im‚m (‘AlÓ) replied to him by saying, "If it were so, there would be no justification of reward or punishment . . . " The Im‚m pointed to the rational principle on which the legislation is based. And at the end he reasoned that All‚h did not create the heavens and the earth and what is between them in vain. If All‚h could will the man's actions in a way as to deprive him of his freedom of will and choice, it would mean that He could do things without any purpose and aim; then He could create the whole creation aimlessly and in vain. This in its turn would render the principle of resurrection and reward and punishment invalid too. It is narrated in at-TawhÓd and ‘UyŻnu ’l-akhb‚r that ar-Rid‚ (a.s.) was asked about compulsion and delegation, and he said: "Should I not teach you in this regard a principle by which you shall never differ (among yourselves), and no one will argue with you on this subject but that you shall defeat him (by it)?" We said: "(Teach it to us) if you so please." Thereupon he said: "Verily All‚h is not obeyed through compulsion, nor is He dis≠obeyed by overpowering; and He did not leave the servants remiss in His kingdom; He (still) owns what He has given into their possession, and has power on what He has put into their power. Now, if the servants decided to obey Him, He would not prevent them from it, nor would he put any obstruction to it; and if they decided to disobey Him, then if He pleased to bar their way to it He would do so, and if He did not hinder it and they com≠mitted it, then it was not He Who led them into that (sin)." Then the Im‚m said: "Whoever would accurately delineate the boundaries of this speech would surely overcome his adversary." †††††††† The author says: Why did "al-Mujabbirah"

( It is correct to say, on the basis of the divine decree and measure, that nothing happens in this world unless it turns an essential being; it is because every thing and every affair comes into being when it is decreed by All‚h, according to the measure prescribed by Him; and then it cannot fail to happen, otherwise the decree of All‚h would fail. At the same time, it should be kept in mind that a transient or possible thing becomes essential because of its sufficient cause. When looked at in conjunction with its sufficient cause, it would be called "essential"; but separated from that cause, it would remain as it was before - a transient or possible thing. Let us look at an action of man which he does by his free will and choice. When we look at it in relation to all things that are necessary to bring it into being - knowledge, will, proper tools and organs, the material, formal, efficient and final causes, and all the conditions of time and space - it will become an essential being; and it is in this context that it become subject of the eternal divine will. In other words, it becomes an essential being when all aspects of its sufficient cause are com≠plete. But, looked in relation to each of those aspects separately, it remains only a transient and possible thing. If it is seen vis-ŗ-vis its efficient cause only, that is, in relation to the doer only, it will retain its characteristics of transience and possibility - it will not become an essential being. It is now clear to see at which point the believers in "com≠pulsion" have deviated from the right path. They thought that, inasmuch as the human action was subject to the divine will and decree, man had no power on it; he was not a free agent; he was rather a helpless tool in divine hands. But they did not take into consideration the fact that the divine will takes it into hand only when all aspects of its sufficient cause are complete, and not before that. The divine will decrees that a certain action be done by Zayd - not unconditionally, but on the condition that it is done by Zayd's free will, at a certain time and a certain place. Therefore, its relation to the divine will itself demands that it should be an action of a free agent, done by his own free will and choice. Doubtlessly, that action will be called an "essential" one if seen in relation to the divine will; but at the same time and by virtue of the same divine will, it will be a possible and transient action when related to the doer, that is, the man. In other words, there are two wills - the human and the divine; they do not run parallel to each other; the divine will comes after and above the human will - they are in a vertical, and not a horizontal position to each other. Therefore, there is no competition or collision between the two wills. It was a short-sightedness on part of the believers in compulsion to negate the human will in order to establish the divine one. The Mu‘tazilites said that human actions are done by man's free will. But they went to the other extreme, and fell in an error no less objectionable than that of al-Mujabbirah. They too said that if human action was subjected to the divine will man would not have any freedom of will and choice. And then they took a position diametrically opposed to that of al-Mujabbirah, and came to the conclusion that the divine will had no relation what≠soever to the human action. Thus they had to accept another creator - the man himself - for human actions. In this way, they accepted dualism without knowing what they were doing. Going further they fell into traps more harmful than the belief of al-Mujabbirah. As the Im‚m has said: "The poor al-Qadariyyah, they wanted to emphasize the justice of All‚h, so they removed Him from His power and authority. . . " A master, showing kindness to one of his slaves, married him to a slave-girl of his; he bestowed on him a property, gave him a well-furnished house and provided him with all the necess≠ities of life. Then there came some people there, looked at his property, and began arguing among themselves. Someone said: "Even though the master has given this property to his slave and has made him its owner, the slave has no right in, or authority over, this property at all. Does any slave own any thing? The slave together with all his belongings belongs to the master." Another said: "No. You are wrong. The master has bestowed on this slave the right of property. Now the slave is its absolute owner, and the master has lost all his rights, and authority over this property. We may say that he has abdicated in favour of his slave. " The former was the opinion of al-Mujabbirah; the later that of the Mu‘tazilites. But both were wrong. The correct view would have been to say: The master has got his status of mastership; the slave his position of servitude and bondage. The master has made the slave owner of his (i.e., master's) property. The property belongs to the master at the same time that it belongs to the slave. There are two ownerships - one over the other. This is what the Im‚ms of Ahlu ’l-bayt (a. s.) have taught us to believe, and what the reason supports. ‘Ab‚yah ibn Rib‘Ó al-AsadÓ asked ‘AlÓ, the Leader of the faithful, the meaning of "capability". The Leader of the faithful asked a counter question: "Do you have that capability without God or with God?" When ‘Ab‚yah remained silent, he told him, "Tell me, O ‘Ab‚yah!" He said: "What should I say? O Leader of the faithful!" He said: "You should say that you have got that capability by (grace of) All‚h, to Whom it belongs and not to you. If He made you its owner, it would be of His bounties, and if He took it away from you, it would be a trial from Him; and He is the Owner of what He gave into your possession, and has power over what He put under your power. . ." (al-Ihtij‚j) The author says: Its meaning may be understood from the preceding explanation. al-MufÓd reports in his Sharhu ’l-‘aq‚’id: It has been nar≠rated from AbŻ ’l-Hasan, the third, (a.s.) that he was asked whether the actions of the servants were created by All‚h. He (a.s.) said: "If He were their creator, He would not have dis≠owned their liability. And He (All‚h) has said: Verily, All‚h is free from liability to the idolators . . . (9:3). It does not mean that All‚h was not responsible for the creation of the idolators; what All‚h has disowned any responsibility of, is their idol≠ worship and their evils." The author says: There are two aspects of a deed - its actual existence, and its relation to its doer. It is only when an action is seen in relation to its doer that it is called obedience or disobedience, good or bad, virtue or sin. So far as actual existence is concerned, there is no difference between marriage and fornication. What distinguishes one from the other is the command of All‚h - marriage conforms with the divine law, and fornication goes against that law. Someone is killed without any reason; another is killed by a lawful authority in reprisal of a murder. A teacher punishes an orphan in order to guide him aright; an oppressor hits at the same orphan unjustly. In all these examples, the actual movements of the actions are identical. But one group is called sin because it does not conform with the divine law or goes against the common weal of the society. All‚h says: All‚h is the Creator of everything. . . (39:62). Every action is a "thing" inasmuch as it exists. And the Im‚m has said: "Whatsoever may be called a thing is created, except All‚h. . ." Also, All‚h says: Who made good everything that He has created. . . (32:7). It may be inferred that everything is good because it is created. Creation and goodness are insepar≠able factors. But at the same time, we see that All‚h has named some actions as evil. For example, He says: Whoever brings a good deed, he shall have ten like it, and whoever brings an evil deed, he shall not be recompensed but only with the like of it . . . (6 :160). These are obviously the actions done by man; not the factor of recompense which cannot apply to divine actions. Such a deed is called sin. It is evil because it lacks some thing; because it is a nullification of a spiritual virtue or social good. In other words, a sin is sin because it is a negation , a non-being; otherwise it would have been good. Now, let us look at the following verses of the Qur’‚n: No misfortune befalls on the earth nor in your own souls, but it is in a book before We bring it into existence. . . (57:22); No affliction comes about but by All‚h’s permission; and who≠ever believes in All‚h, He guides aright his heart . . . (64 :11); And whatever affliction befalls you, it is on account of what your hands have wrought, and (yet) He pardons most (of your faults) (42:30); Whatever benefit comes to you, it is from All‚h, and whatever misfortune befalls you, it is from yourself (4:79); . . . and if a benefit comes to them, they say: "This is from All‚h;”- and if a misfortune befalls them they say: "This is from you." Say: “All is from All‚h;" but what is the matter with these people that well-nigh they do not understand what is told (them)? (4:78). On pondering upon these verses, it be≠comes clear that these misfortunes are relative evils. A man is bestowed with the bounties of All‚h, like security and peace; health and wealth, and so on; then he loses one or more of these bounties. This misfortune, in relation to that man, is evil because it has nullified some existing things, that is, the bounties which he had previously enjoyed. Thus, every misfortune is created by All‚h, and at that stage it is not an evil. But it is an evil when seen in relation to the man who loses an existing bounty because of it. Likewise, every sin is a negative factor, and as such, it is not to be attributed to All‚h at all; though it may be attributed to Him from another angle, inasmuch as it happens by permission of All‚h. al-Bazanti said: I told ar-Rid‚ (a.s.) that some of our fellows believe in compulsion and some of them advocate the (belief of) capability. Thereupon he told me: "Write down (as I say): All‚h, Blessed and High is He, has said: ‘O son of Adam! By My will you have become such that you wish for yourself what you wish; and by My power you discharged the duties imposed by Me (on you); and by My bounty, you got power to disobey Me; I made you hearing, seeing (and) powerful. Whatever benefit comes to you, it is from All‚h; and whatever misfortune befalls you, it is from yourself. And it is as it is because I have more right on your good deeds than you have yourself; and you are more liable to your sins than Me. And it is because I cannot be questioned concerning what I do and they shall be questioned. Thus, I have arranged for you everything that you want. . .' " (Qurbu ’1-asn‚d) This, or nearly the same, tradition is narrated through other chains, of the SunnÓs as well as of the ShÓ‘ahs. In short, the deeds that cannot be attributed to All‚h, are the sins per se. It further explains the sentence of the preceding tradition: "If he were their creator, He would not have disowned their liability . . . What All‚h has disowned any responsibility of, is their idol-worship and their evils. . . " AbŻ Ja‘far and AbŻ ‘Abdill‚h (a.s.) said: "Certainly, All‚h is too Merciful to His creatures to compel them to sin and then to punish them for it. And All‚h is too powerful for anyone to think that He would will a thing and it would not happen!" (The narrator) said: "Then they (a.s.) were asked: ‘Is there a third position between the (positions of) compulsion and (in≠dependent) capability?' They said: ‘Yes, broader than (the space) between the heaven and the earth."' (at-TawhÓd) Muhammad ibn ‘Ajl‚n said: "I asked AbŻ ‘Abdill‚h (a.s.) whether All‚h has delegated (the authority of) the affair to the servants. He said: All‚h is too honourable to delegate (the auth≠ority) to them.’ I said: ‘Then has He compelled the servants in their deeds?’ He said: All‚h is too just to compel a servant on a deed and then to punish him for it.’” (ibid.) In the same book Mihzam is reported as saying: "AbŻ ‘Abdill‚h (a.s.) said: "Tell me what is that concerning which our followers (whom you have left behind) have differed among themselves.’ I said: ‘About the compulsion and the delegation?’ He said: ‘Then ask me about it.’ I asked: ‘Has All‚h compelled the servants to (commit) sins?’ He replied: ‘All‚h is too over≠powering to do it to them.’ I asked: ‘Then has He delegated (the authority) to them?’ He replied: ‘All‚h has too much power over them to do so.’ I asked: ‘Then what is it (i.e., the correct position)? May All‚h make your affairs right for you!’" (The narrator says:) "The Im‚m turned his hand twice or thrice, then said: ‘If I were to answer you concerning it, you would not believe.’” The author says: “All‚h is too overpowering to do it to them”: Compulsion means that a force majeure subdues the subject in such a way that his power of action is nullified. "Too overpowering" (or, more overpowering than that) is the predomi≠nant will of All‚h - He has willed that the action would emanate from the doer by his free will and choice, and this is what is actually happening in the world. The divine will has given the man freedom of will; neither the divine will negates the human will, nor the human will collides with the divine will. It is reported in at-TawhÓd that as-S‚diq (a. s.) said: "The Apostle of All‚h said: ‘Whoever thinks that All‚h enjoins the evil and indecency, he tells a lie against All‚h; and whoever believes that the good and bad (do happen) without the will of All‚h, he removes All‚h from His authority.'" It is reported that al-Hajj‚j ibn YŻsuf wrote to al-Hasan al-BasrÓ, ‘Amr ibn ‘Ubayd, W‚sil ibn ‘At‚’ and ‘Amir ash-Sha‘bÓ, asking them to describe what they had got (and what has reached them) in respect of (divine) decree and measure. al-Hasan al-BasrÓ wrote to him: "The best thing that has reached me is that which I heard the Leader of the faithful, ‘AlÓ ibn AbÓ T‚lib (a.s.) saying: ‘Do you think that He Who has forbidden you has (also) acted cunningly against you? Rather, your lower and higher (parts) have cunningly deceived you, and All‚h is free from its liability.'" And ‘Amr ibn ‘Ubayd wrote to him: "The best thing I have heard about the decree and measure is the saying of the Leader of the faithful, ‘AlÓ ibn AbÓ T‚lib (a.s.): ‘If perfidy were in reality decreed, the perfidious man, if punished, would have been op≠pressed.' " And W‚sil ibn ‘At‚’ wrote to him: "The best I have heard about the decree and measure is the saying of the Leader of the faithful, ‘AlÓ ibn AbÓ T‚lib (a.s.) : ‘Do you think that He would guide you to the path and (then) obstruct you (from moving on)?' " And ash-Sha‘bÓ wrote to him: "The best thing I have heard concerning the decree and measure is the word of the Leader of the faithful, ‘AlÓ ibn AbÓ T‚lib (a. s.) : ‘Whatever you have to seek All‚h's pardon for it, it is from you; and what≠ever you thank All‚h for it, it is from Him.' " When their letters reached al-Hajj‚j and he studied them, he said: "Certainly they have taken it from a clear spring." (at-T‚r‚’if ) It is narrated in the same book that someone asked Ja‘far ibn Muhammad as-S‚diq (a. s.) about the decree and measure, and he replied: "Whatever you may blame the servant (of All‚h) for it, it is from him; and whatever you cannot blame the servant (of All‚h) for it, it is the work of All‚h. All‚h will say to the servant: ‘Why did you disobey? Why did you transgress? Why did you drink liquor? Why did you fornicate?' This is, therefore, the work of the servant. But He will not say to him: ‘Why were you sick? Why were you of short stature? Why did you become white? Why were you black?(He will not ask it) because it is the work of All‚h." ‘AlÓ (as.) was asked about monotheism and justice (of All‚h), and he said: "Monotheism is that you should not imagine Him; and justice is that you should not accuse Him." (Nahju ’1-bal‚ghah) The author says: There are numerous traditions on this subject; but those quoted above throw light on all the aspects of the topic. The above-mentioned traditions show various special methods of argument regarding the subject matter. a) Some of them argue on the basis of legislation itself - order and prohibition; punishment and reward etc. - that man has freedom of will, without any compulsion or delegation of power. See, for example, the speech of the Leader of the faithful, ‘AlÓ (as.), replying to the old man. It is similar to the argument we have inferred from the words of All‚h. b) Others bring in evidence the verses of the Qur’‚n which cannot be reconciled with the theory of compulsion or delegation of power. For example: And All‚h’s is the kingdom of the heavens and the earth (3:189); and your Lord is not in the least unjust to the servants (41:46). Also, there is the verse, Say: "Surely All‚h does not enjoin indecency" (7:28) . Poser: A deed may be described as unjust or indecent if it is seen in relation to us. But when it is attributed to All‚h it is not called unjust or indecent. Therefore, even if all "our" deeds were actually done by All‚h, it would be perfectly right to say that He is not unjust and does not enjoin indecency. Reply: The sentence seen in the context leaves no room for such misconceptions. The complete verse is as follows: And when they commit an indecency they say: "We found our fathers doing this and All‚h has enjoined it on us " Say: "Surely All‚h does not enjoin indecency. Do you say against All‚h what you do not know?" Look at the sentence, "and All‚h has enjoined it on us". The pronoun "it" clearly refers to the indecency committed by them; and it is the same deed which is referred to in the sentence, "Surely All‚h does not enjoin indecency,". All‚h does not enjoin what is termed as indecency in context of human activities; it does not matter whether in other framework it is called indecency or not. c) A third type of reasoning is based on the divine attributes. All‚h has given Himself many good names, and has described Himself with many sublime attributes, which cannot be squared with compulsion or delegation of power. All‚h is the Subduer, the Omnipotent, the Benevolent and the Merciful. These attributes can only be believed in if one believes that everything depends on All‚h in its existence, and that its defects and shortcomings can≠not be attributed to Him at all. (Refer to the traditions quoted from at-TawhÓd.) d) Yet others refer to seeking the pardon of All‚h as well as to the blame which society directs at the wrong-doer. If sin were not from the man himself, there would have been no mean≠ing in asking for divine pardon. If all our actions were done by All‚h why should we be blamed for only some of them and not for the others? e) Lastly, there are the traditions which explain the words, like causing to err, sealing the hearts and misleading, when they are attributed to All‚h: ar-Rid‚ (a.s.) said explaining the words of All‚h, and He (All‚h) left them in utter darkness - they do not see: "All‚h is not described as leaving something as His creatures do. But when He knew that they would not return from disbelief and error, He held back His help and grace from them and let them alone with their choice." (‘Uyunu ’1-akhb‚r) The same book narrates from the same Im‚m in explanation of the words of All‚h, All‚h has set a seal upon their hearts: "It is setting a seal on the hearts of the disbelievers as a punishment of their disbelief, as All‚h has said: . . . nay! All‚h has set a seal upon them owing to their disbelief, so they shall not believe except a few (4:155)." as-S‚diq (a.s.) said concerning the words of All‚h, Surely All‚h is not ashamed to set forth any parable. . .: "This divine word answers those who think that All‚h makes (His) servants go astray and then punishes them for that straying . . . " (Majma‘u ’l-bay‚n) The author says: Its meaning may be understood from previous explanations.

A PHILOSOPHICAL DISCUSSIONEvery species is related to a particular type of action and reaction. In fact it is these special characteristics which identify the species as such. We looked at various kinds of actions and reactions emanating from various groups. Our reason told us that there should be an efficient cause, an agent, to bring each kind of these actions and reactions into being. Therefore, we put every group in a separate category, identifying it as a species. When we compared human characteristics, for example, with those of an animal, and delineated them clearly, we decided that they were two different species, with different characteristics. When the actions are seen in relation to their subjects, that is, the species, they are primarily divided into two categories: First: The actions emanating from the nature - where the knowledge of their emanation has no effect at all on their existence. For example, the growth and nutrition of the vegetables; the movement of the bodies; our own health or illness. These things are known to us, present in our own bodies; but our knowing or not knowing them has no effect whatsoever on their coming into being; they totally depend upon their doer - that is, nature. Second: The actions issuing forth from the doer with his knowledge - where the said knowledge has a bearing on their being, like the intentional actions of the man and even of some animals. The doer does such an action after knowing and identifying it; and it is the knowledge and perception that gives him that insight. The knowledge makes him realize what would consti≠tute his perfection, and helps him in deciding whether a particular action would lead to that desired perfection. The knowledge distinguishes the means of perfection from other things; and this distinction helps the doer in choosing a particular course of action. And the action comes into being. The activities based upon ingrained aptitude (like issuing forth of the required voices, when a man speaks), as well as those emanating from natural disposition, or from the dictates of nature (like breathing) and, likewise, those springing from overwhelming grief or fear etc., do not require contemplation or meditation by the doer. Why? Because there is not more than one form of knowledge here, and the doer does not have to delay his activity awaiting a final decision. Therefore, he does it immediately. But in other cases, where the doer has before his eyes two or more possible forms of knowledge to choose from, he has to spend at least a few moments in contemplation and deliberation. For example, Zayd is hungry, and he gets a bread. Its one aspect is that it may satiate his hunger; but there may be other aspects too - it may be another man's property, it may be poisoned, it may have become dirty and so on. Zayd has to reflect whether the bread is legally, morally and hygienically fit for consump≠tion. When he reaches a conclusion, the actions follows without any delay. The first type of activities is called involuntary, like natural reactions; the second type is called voluntary, or intentional, like walking or talking. The intentional actions, emanating from man's knowledge and will, are again divided into two categories: First: When the man decides to do - or, not to do - a certain work, he may do so entirely on his own, without being influenced by any other fellow. In the example given above, Zayd may decide, on his own, not to eat the bread because it was someone else's property; or he may eat it in spite of that snag. This is called a deed done by man's free will. Second: When the man opts for a certain course of action under the influence of someone else. A tyrant may force a help≠less person to act according to that tyrant's instruction under duress. The poor fellow in this condition commits sins and crimes against his own will. This is called a deed done under compulsion. Right? But let us look at this second category more closely. We have said that this kind of deed results from the compeller's compulsion; he does not allow any freedom to the doer, who has to take the only way left open by the oppressor. But even then, it is the doer himself who decides to proceed on that way. It is true that the major factor leading to this decision was the tyrant's compulsion; but it is equally true that the decision was taken by the doer himself, even though it was taken to save himself from the tyrant's oppression. In short, even the deeds done under compulsion are done by the will of the doer. It follows that the division of intentional actions into these two categories is not real, not based on actual facts. The intentional action is the one which emanates from a knowledge and a will that tips the bal≠ance in its favour. This reality is found in the deed done under compulsion as well as in the one done by free will. It makes no difference that it was some other man's force or fear that tipped the balance in one case and the doer's own thinking that did so in the other. A man sitting near a wall looks up to find that it was about to fall; overcome by fear he sprints away from that place. And we say that he did so by his own free will. Suppose, a tyrant threatens to bull-doze the wall over him if he did not move away. Overcome by fear, he sprints away from there. And we say that it was done under compulsion. But the funda≠mentals in both cases are the same. The man is overcome by fear and decides to move away. So, why should we put them in two different categories. Objection: There is enough difference between the two actions to warrant their assignment to two different categories. The deed done by free will is based on its underlying wisdom (in the eyes of the doer); the doer deserves praise or blame, and gets reward or punishment, for it. All these factors are simply absent in the case of a deed done under compulsion. Reply: It is true. But these factors are based on subjective approach of the society. They do not have any existence outside the imagination. By talking on these subjective approaches we have crossed the limits of philosophy. Philosophy deals with the things that exist in reality, as well as with those things' natural characteristics. What all this leads to is the conclusion that the discussion whether man is free in his actions is beyond the scope of philosophy. We may yet bring it back on the track of philosophy from another direction: A transient (possible) thing has equal relation with existence and non-existence. It, therefore, needs a sufficient cause to tip the balance in favour of existence, so that it may come into being. The transient thing, when related to its sufficient cause, becomes an essential being - it becomes impossible for it not to exist. That is why it is said that a transient does not come into being unless it becomes an essential being. A transient, by its definition, must have a sufficient cause for its existence. A transient existing without its sufficient cause is a contradiction in terms. And that cause gives it the essentiality, so long as it exists. Now look at the universe at a glance. You will find a chain made up of unnumerable links, all of which would be essential beings. In other words, not a single existing thing could be called a transient, so long as it exists. But this "essential - ness" comes to it only when it is looked at in relation to its sufficient cause. The sufficient cause may be a single thing or a compound of various causes - the material, the formal, the efficient and the final causes, plus the necessary conditions of time and space as well as other preliminaries. An effect when related to its sufficient cause must invariably exist - because the said cause would make it essential. But when seen with only a part of that cause, or if related to any outside factor, it would not be essential; it would remain a transient as before. If a transient, on being related to only a part of its sufficient cause (e.g., to its efficient cause only) become essential and come into being, its sufficient cause would be superfluous; and it would be a contradiction in term. It shows that in this natural world two systems are found simultaneously: one of essentiality and the other of transiency. The system of essentiality covers the sufficient causes and their effects - there is no transiency in any part of this world, neither in any person nor in any action. The system of transiency per≠meates the matter and its potentialities when related to only a part of the sufficient cause. Take any human action; if it is related to its sufficient cause - man (the efficient cause), knowledge and will (the final), matter (the material) and its shape (the formal) plus all conditions of time and space including removal of every hindrance - it would become essential. But if it is seen in relation to only its efficient cause, that is, man, it would remain transient. Finally, it should be pointed out that the transient things need a cause for their existence because of their transiency. And this need would not end until the chain of cause and effect finally reaches a cause Who is the Essential Being. This observation leads to the following two conclusions: First: The need of an effect for its cause does not end on its being related to its transient cause. The need continues until it reaches the Final Cause, the Essential Being. Second: This need emanates from its transient nature. It needs a cause to bring it into existence with all its character≠istics and traits, including its relationship with its various causes, fulfilling all the conditions of its existence. Now we may ponder upon the question of compulsion and delegation of power, keeping in view the above-mentioned premises: First: No delegation of power: Man, like all other things and their actions, depends on the will of All‚h, for his existence. In the same way, man's action depends on the will of All‚h in its existence. Therefore, the Mu‘tazilites' view - that human actions have no relation at all to the divine will - is completely baseless. There was no reason at all for them to deny the decree and measure of All‚h in respect of the man's actions. Second: No compulsion: This relation to the will of All‚h, inasmuch as it is concerned with existence, keeps all the char≠acteristics of the created thing in view. Every effect emanates from its cause - with all its characteristics which have any bearing on its existence. A man's creation is attributed to All‚h, keeping in view all its intermediary causes and condition - the father, the mother, the time, the place, the features, the quantity, the quality and a lot of other concomitants. Likewise, the action of man is attributed to All‚h, keeping in view all its characteristics and conditions. When a man's action is attributed to All‚h and His will, it does not cease to be the man's action; it is still caused by the said man's will. The will of All‚h decrees that the action be done by the man emanating from the man's own free will and choice. Therefore, it would be a contradiction in term to say that the action was no longer done by man's free will because it was related to the divine will. All‚h Himself has decreed it to be a work of the man by his free will; how can it be said that the divine will lost its effectiveness and the action happened without the man's free will? It is now clear that the view of al -Mujabbirah - that the human action's relation to the divine will nullifies its relation to the human will - is absolutely devoid of truth. The above discourse shows that the said action has a relation to the human will and a relation to the divine will; neither relation nullifies the other, because each is connected with the other vertically, not horizontally. Third: The human action, when related to its sufficient cause; becomes essential. But seen in relation to only a part of the sufficient cause, it remains transient. For example, when the action is related to only its sufficient cause, that is, man, it does not become essential, but remains transient as before. Therefore, what a group of modern materialist philosophers have said - that the whole system of nature is permeated by compulsion, and there is no free will at all in the universe - is totally wrong. As we have said, all effects in relation to their sufficient causes are essential, but, when related to only a part of the said causes, are transient. And it is the foundation on which man's life is based. A man teaches and trains his child and then hopes that his efforts would bear fruit. If there was no freedom in the world, if everything was essential and had to happen any≠how, then all this teaching and training would be of no earthly use; there would remain no place for hope in human life. |