|

|

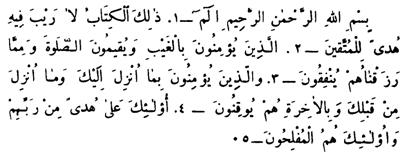

Al-Mizan Allamah as-Sayyid Muhammad Husayn at-Tabataba'i Chapter 3 Chapter Twoal Baqarah (The Cow) 286 verses – Medina In the name of All‚h, the Beneficent, the Merciful. Alif L‚m mÓm (1) . This Book, there is no doubt in it, (is) a guidance to those who guard (against evil) (2), Those who believe in the unseen and keep up the prayer and spend (benevolently) out of what We have given them (3), And who believe in that which has been sent down to thee and that which was sent down before thee and they are sure of the hereafter (4). These are on a guidance from their Lord and these it is that shall be the successful ones (5).

GENERAL COMMENTThis chapter was revealed piecemeal; therefore, it does not have a single theme. However a major part of it shows a general objective: It emphasizes that a man cannot be a true servant of All‚h unless he believes in all that was revealed to the apostles of All‚h without making any difference between revelation and revelation, or between apostle and apostle; accordingly, it admon≠ishes and condemns the disbelievers, the hypocrites and the people of the book because they differed about the religion of All‚h and differentiated between His apostles; thereafter it ordains various important laws, like change of the direction to which the Muslims were to turn for their prayers, regulations of hajj, inheritance and fasting and so on. COMMENTARY QUR’ĀN: Alif l‚m mÓm: God willing, we shall describe in the 42nd chapter some things related to the "letter-symbols" that come at the beginning of some chapters. Also, the meaning of the guidance of the Qur’‚n and of its being a book will be ex≠plained later on. QUR’ĀN: This Book, there is no doubt in it, (is) a guidance to those who guard (against evil), those who believe in the unseen: Those who guard against evil, or in other words, the pious ones, are the very people who believe. Piety, or guarding oneself against evil, is not a special virtue of any particular group of the believers. It is not like doing good, being humble before God or purity of intention, which are counted as various grades of the faith. Piety, on the other hand, is a comprehensive virtue that runs through all the ranks of the true faith. It is for this reason that All‚h has not reserved this adjective for any particular group of the believers. The characteristics of piety, enumerated in these four verses, are five: Believing in the unseen, keeping up prayers, spending benevolently out of what All‚h has given, believing in what All‚h has revealed to His apostles, and being sure of the hereafter. The pious ones acquire these spiritual qualities by a guidance from All‚h, as All‚h tells us in the next verse: "These are on a guidance from their Lord ". They became pious and guarded themselves against evil because All‚h had guided them to it. When they got that quality, the Qur’‚n became a guidance for them: "This Book . . . (is) a guidance to those who guard against evil". It clearly shows that there are two guidances, one before they became pious, the other after it. The first guidance made them pious; and thereupon All‚h raised their status by the guid≠ance of His Book. The contrast is thus made clear between the pious ones on one hand and the disbelievers and the hypocrites (who are admonished in the next fifteen verses) on the other. The later two groups are surrounded by two strayings and two blindnesses. Their first straying causes their unbelief and hypocrisy, and the second one (which comes after their unbelief and hypocrisy) confirms their first error and strengthens it. Look at what All‚h says about the disbelievers: All‚h has set a seal upon their hearts and upon their hearing; and there is a covering over their eyes (2:7) . Sealing their hearts has been ascribed to All‚h, but the covering over their eyes was put by the disbelievers themselves. Likewise, All‚h says about the hypocrites: There is a disease in their hearts, so All‚h added to their disease (2:10). The first disease is attributed to the hypocrites themselves, and the second one to All‚h. The same reality has been explained in many verses. For example: He causes many to err by it and many He leads aright by it! But He does not cause to err by it (any) except the transgressors (2:26) ; . . . but when they turned aside, All‚h made their hearts turn aside (61:5). In short, the pious ones are surrounded by two guidances, as the disbelievers and hypocrites fall between two errors. The second guidance is by the Qur’‚n; therefore, the first one must have been before the Qur’‚n. They must have been guided by a healthy and unimpaired psychology. If a man's nature is faultless and flawless, it cannot fail to see that it is dependent on some thing above it. Also, it realizes that every other thing, which it may perceive, imagine or understand, depends likewise or, a thing outside the chain of dependent and needy things. Thus, it comes to believe that there must be a Being, unseen and imperceptible through the senses, who is the beginning and end of every other thing. It also sees that the said Essential Being does not neglect even the smallest detail when it comes to creative perfection of His creatures. This makes him realize that the said Creator cannot leave the man to wander aimlessly hither and thither in his life; that He must have provided for him a guidance to lead him aright in his actions and morals. By this healthy reasoning, the man acquires the belief in One God, in the institu≠tion of prophethood and in the Day of Resurrection. In this way, his faith in the fundamentals of religion becomes complete. That faith leads him to show his servitude before his Lord, and to use all that is in his power - wealth, prestige, knowledge, power, and any other excellence - to keep this faith alive and to convey it to others. Thus we come to the prayer and benevolent spending. The five virtues enumerated in these verses are such that a healthy nature unfailingly leads the man to them. Once a man reaches this stage, All‚h bestows on him His another grace, that is, the guidance by the Qur’‚n. The above-mentioned five qualities - correct belief and correct deeds - fall between two guidances, a preceding one and a following one. This second guidance is based on the first one. This fact has been described in the following verses : All‚h confirms those who believe with the sure word in this world's life and in the hereafter (14:27). O you who believe! fear All‚h and believe in His apostle. He will give you two portions of His mercy, and make for you a light with which you will walk . . . (57:28). O you who believe! if you help All‚h, He will help you and make firm your feet (47:7) . And All‚h does not guide the unjust people (61:7) . . . . and All‚h does not guide the transgressing people (61:5).The same is the case with error and straying of the dis≠believers and hypocrites, as will be seen later on. The above verses give an indication that man has another life, hidden behind this one. It is by that life that he lives in this world as well as after death and at resurrection. All‚h says: Is he who was dead then We raised him to life and made for him a light by which he walks among the people, like him whose likeness is that of one in utter darkness whence he cannot come forth . . . (6:122). We shall explain it, God willing, later on. Those who believe in the unseen" "al- Īm‚n”

( It has already been explained

that faith has many grades. Sometimes one is certain of the object of faith;

and this certainty has its effects; at other times the certainty increases and

includes some concomitants of the said object; and at times it increases to include

all the related matters of the object of faith. Naturally, the belief, thus, is

of various grades and so are the believers. "al-Ghayb" ( The Qur’‚n emphasizes that man should not confine his knowledge and belief to only the perception; it exhorts him to follow healthy reasoning and rational understanding. QUR’ĀN: and they are sure of the hereafter: Instead of only believing in the hereafter, they are sure of it. There is an indication here that one cannot be pious, cannot guard himself against evil, until he is really certain of the hereafter - a certainty that does not let him forget it even for a short time. A man believes in a matter, yet sometimes forgets some of its demands and then com≠mits something contrary. But if he believes in, and is sure of, the day when he shall have to give account of all that he has done -big or small - he will not do anything against the divine law, will not commit any sin. All‚h says: . . . and do not follow desire, lest it should lead you astray from the path of All‚h; (as for) those who go astray from the path of All‚h, for them surely is a severe punishment because they forgot the day of reckoning (38:26). Clearly it is because of forgetting the Day of Reckoning that man goes astray. It follows that if one remem≠bers it and is sure of it, he will surely guard himself against evil, will become pious. QUR’ĀN : These are on guidance from their Lord and these it is that shall be the successful ones: Guidance is always from All‚h, it is not ascribed to anyone else except in a metaphorical way. All‚h describes His guidance in these words: Therefore (for) whomsoever All‚h intends that He would guide him aright, He expands his breast for Islam . . . (6 :125) . If one's breast is expanded, he will be free from every tightness and niggardliness. And All‚h says that: . . . whoever is preserved from the niggard≠liness of his soul, these it is that are the successful ones (59:9). Therefore, He says in this verse about those who are on His guid≠ance that "they shall be the successful ones". TRADITIONS as-S‚diq (a.s.) said about the words of All‚h: Those who believe in the unseen: "Those who believe in the rising of al- Q‚'im ( The author says: This explanation is given in other traditions also; and it is based on the "flow" of the Qur’‚n. According to at-TafsÓr of al-`Ayyashi, as-S‚diq (a.s.) said about the words of All‚h: and spend (benevolently) out of what We have given them, that it means: the knowledge We have given them. In Ma`‚ni 'l-akhb‚r, the same Imam has explained it in these words: "And they spread the knowledge We have given them and they recite what We have taught them of the Qur’‚n. The author says: Both traditions explain the "spending" in a wider sense that includes spending the wealth as well as using other bounties of All‚h in His cause; the explanation given by us earlier is based on this exegesis. A PHILOSOPHICAL DISCUSSION Should we rely on rational concepts, in addition to the things perceptible through the senses? It is a subject of great con≠troversy among the western scholars of the later days. All Muslim philosophers as well as most of the western ones of ancient times believed that we can rely on the rational as well as the sensual perceptions. They were rather of the opinion that an academic premises does not look at a tangible and sensual factor as such. But most of the modern scholars, especially the scientists, hold that nothing can be relied upon except what one perceives through the five senses. Their proof is as follows: Pure rational proofs often go wrong. There is no test or experiment, perceptible through the senses, to verify those rational proofs or their premises. Sensual perceptions are free from this defect; when we per≠ceive a thing through a sense, we verify it through repeated tests and experiments; this testing continues till we are sure of the characteristics or properties of the object of test. Therefore, sensual perception is free from doubt, while rational proof is not. But this argument has many flaws: First: All the above-mentioned premises are rational; they cannot be perceived by any of the five senses. In other words, these scholars are using rational premises, to prove that rational premises cannot be relied upon! What a paradox! If they succeed in proving their view-point through these premises, their very success would prove them wrong. Second: Sensual perception is not less prone to error and mistake than rational proof. A cursory glance at the books deal≠ing with the optics and other such subjects is enough to show how many errors are made by sight, hearing and other senses. If rational proof is unreliable because of its possible mistakes, sensual perception also should be discarded for the same reason. Third: No doubt, there should be a way to distinguish the right perception from the wrong. But it is not the "repeated testing", per se, that creates that distinction in our mind. Rather, it becomes one of the premises of a rational proof which in turn provides that distinction. When we discover a property of an object, and the property remains the same through repeated tests, a rational proof, on the following lines, is offered by our think≠ing power. If this property were not this thing's own property, it would not be found in it so unfailingly; But it is always found in it without fail; Therefore, it is its own property. It is now obvious that sensual perception too depends on rational premises to finalize its findings. Fourth: Let us admit that practically every sensual per≠ception is supported by test. But is that test verified by another test? If yes, then the same question will arise about this later one. Obviously, it cannot go on ad infinitum; there must come at the end a test whose verification depends not on a visible test but on the above-mentioned rational proof. It means that one cannot rely on sensual perception without relying on ration≠al concepts. Fifth: The five senses cannot perceive absolute and major issues; they know only the particular and minor things. Know≠ledge depends on absolute issues, which cannot be tested in a laboratory nor can they be grasped by the five senses. A professor of anatomy operates upon, or dissects, a number of living or dead human bodies - it does not matter how large or small that number is. He finds that each of the bodies - which he has opened - has a heart, a liver and the like. And after looking at those particular cases, he feels bold enough to teach an absolute proposition that all men have a heart and a liver. The question is: Has he seen in≠side "all" the human beings? If only that much can be relied upon which is perceived by the five senses, how can any absolute proposition of any branch of science be accepted as true? The fact is that sensual perception and rational concept both have their place in the field of knowledge; both are com≠plementary to each other. By rationality and understanding, we mean that faculty which is the source of the above examples of absolute principles. Everyone knows that man has such a faculty. How can a faculty created by All‚h (or as they say, by nature) be always in wrong? How can it always fail in the function en≠trusted to it by the Creator? The Creator never entrusts any work to an agent until He creates a connecting link between them. So far as mistakes in rational and sensual faculties are con≠cerned, the reader should look for it in related subjects like logic etc. ANOTHER PHILOSOPHICAL DISCUSSION Man in his early childhood perceives the objects around him; he knows them without knowing that he knows, that is, without being aware that he has, or is using, a faculty called knowledge or cognition. This continues until a time comes when he finds himself doubting or presuming a thing. Then he realizes that before that he was using "knowledge" in his life affairs. He also gradually comes to understand that his perception or con≠cepts are sometimes wrong, that error cannot be in the materials that he perceives - because those material things are facts and facts cannot be non-facts, that is, cannot be wrong. Therefore, the error must be in his perception. When there is no error in perception, it is knowledge - a perception that leaves no room for opposite ideas. By these stages, he becomes aware of the basic principle that positive and negative are mutually exclusive and totally exhaustive; they are contradictories, they cannot both be pre≠sent nor can both be absent. This fundamental truth is the foundation-stone of every self-evident or theoretical proposition. (Even if one doubts this statement, he intuitively knows that this "doubt" cannot be present with its negative, with its "non≠doubt".) Man relies on knowledge in every academic theory and practical function. Even when he feels doubtful about a matter, he identifies that doubt by knowing that it is a doubt. The same applies when he does not know, or only presumes, or merely imagines a thing, he identifies it by the knowledge that it is ignorance, presumption or imagination. But in ancient Greece, there arose a group, the Sophists, who denied existence of knowledge. They showed doubt in every thing, even in their own selves, even in that doubt. The Sceptics of later days are almost their successors. They deny knowledge of every thing outside their own selves and their own minds. Their "arguments" run as follows: First: The most potent knowledge (that comes through the five senses) is often wrong and in error. Then how can one be sure of the knowledge obtained through other sources? How can we rely, in this background, on any knowledge or proposition outside our own selves? Second: When we wish to comprehend any outside object, what we get is merely its knowledge; we do not grasp the object itself. Then, how can it be possible to grasp any object? Reply to the First Argument: First: This argument negates and annihilates itself. If no proposition can be relied upon, how can one rely on the propositions and premises used in this argument? Second: To say that a source of knowledge is "often" wrong, is to admit that it is also correct many times. Then how can it be rejected totally? Third: We have never said that our knowledge is always correct. The Sophists and the Sceptics affirm that no knowledge is correct. To refute this universal negative proposition, a particu≠lar affirmative proposition is sufficient. That is, we have only to prove that some knowledge is correct; and we have done so in the second reply. Reply to the Second Argument: The issue in dispute is knowledge, which means to unveil an object. The Sceptics admit that when they try to comprehend an object, they get its know≠ledge. Their only complaint is that they do not grasp the object itself. But nobody has ever claimed that knowledge means grasping the object itself; our only claim is that knowledge un≠veils some of the realities of its object, that is, of the thing so known. Moreover, the Sceptic refutes his own views practically in every movement and at every moment. He claims that he does not know anything outside his own self, outside his own mind. But when he is hungry or thirsty, he moves to the food or water; when he sees a wall falling down, he runs away from it. But he does not try to get food when he just thinks about hunger, and does not run away when he just thinks about a falling wall. It means that he does not act on the pictures in his mind - which he claims are the real things, and acts on that feeling or percep≠tion which comes to him from outside - which, according to him, does not have any reality and should not be relied upon! There is another objection against existence of knowledge. They deny existence of established knowledge; and have laid the foundation of today's natural sciences on this rejection. Their reasoning is as follows: Every single atom in this world is in constant movement; every single thing is continuously moving towards perfection or deterioration. In other words, what a thing was at a given instant, is not the same in the next. Understanding and perception is a function of brain. Therefore, it is a material property of a material compound. Naturally, this process too is governed by the laws of change and development. It means that all functions of brain, including knowledge, are constantly changing and developing. It is, therefore, wrong to say that there is any such thing as estab≠lished knowledge. Whatever knowledge there is has only relative permanence - some propositions last longer than others. And it is this impermanent conception that is called knowledge. Reply: This argument is based on the presumption that knowledge is not non-material and abstract; that it is a physical thing. But this supposition is neither self-evident nor proved. Knowledge is certainly non-material and abstract. It is not a physical and material thing, because the attributes and properties of matter are not found in it: 1. All material things are divisible; knowledge, per se, is not divisible. 2. Material things depend on space and time; knowledge, per se, is independent of space and time. An event happens in a certain place and time, but we may comprehend it in any place and at any time without any adverse effect on its comprehension. 3. Material things are admittedly governed by the law of general movement and constant change. But knowledge, per se, does not change. Knowledge, as knowledge, is incompatible with change, as one may understand after a little meditation. 4. Suppose that knowledge, per se, is subject to constant change like matter and material things. Then one thing or event could not be comprehended with the same details, in exactly the same way, at two different times. Nor could a past event be remembered correctly later on. Because, as the materialists have said, "what a (material) thing was at a given instant is not the same in the next". These comparisons show that knowledge, as knowledge, is not a material or physical thing. It must be told here that we are not talking about the physical actions and reactions which an organ of a sense or the brain has to undergo in the process of acquiring knowledge. That action and reaction is a process, or a tool, of knowledge, it is not the knowledge itself. For more detailed discussion of this subject one should study the philosophical works. |