|

|

Sociology of the Qur'an Murtadha Mutahhari - 3 - Part 5: Society and Tradition If society has real existence, it should naturally possess laws peculiar to it. If we accept the first theory about the nature of society (which we have already discussed) and reject the existence of society as a real entity, naturally we have to admit that society lacks laws which may govern it. And if we accept the second theory and believe in artificial and mechanical composition of society, then we would have to admit that society is governed by laws but that its laws are confined to a series of mechanical and causal relationships between its various parts, without the distinguishing features and particular characteristics of life and living organisms. And if we accept the third point of view, we shall have to accept, firstly, that society itself has a comparatively more permanent existence independent of the existence of individuals although this collective life has no separate existence, and is distributed and dispersed among its individual members, and incarnates itself in their existence. It has discoverable laws and traditions more permanent and stable than those of the individuals, who are its components. Secondly, we shall have to accept also that the components of society, which are human individuals, contrary to the mechanistic point of view, lose their independent identity‑although in a relative fashion‑to produce an organically composite structure. But at the same time the relative independence of the individual is preserved; because individual life, individual nature, and individual achievements are not dissolved totally in the collective existence. According to this point of view, man actually lives with two separate existences, two souls, and two "selves." On the one hand, there are the life, soul, and self of the human being, which are the products of the processes of his essential nature; on the other, there are the collective life, soul, and self which are the products of social life, and pervade the individual self. On this basis, biological laws, psychological laws, and sociological laws, together, govern human beings. But according to the fourth theory, only a single type of laws govern man, and these are the social laws alone. Among the Muslim scholars `Abd al‑Rahman ibn Khaldun of Tunisia was the first and the foremost Islamic thinker to discuss clearly and explicitly the laws governing the society in independence from the laws governing the individual. Consequently he asserted that the society itself had a special character, individuality, and reality. In his famous introduction to history, he has discussed this theory in detail. Among the modern scholars and thinkers Montesquieu (the French philosopher of the eighteenth century A.D.) is the first to discuss the laws which control and govern human groups and societies. Raymond Aron says about Montesquieu: His purpose was to make history intelligible. He sought to understand historical truth. But historical truth appeared to him in the form of an almost limitless diversity of morals, customs, ideas, laws, and institutions. His inquiry's point of departure was precisely this seemingly incoherent diversity. The goal of the inquiry should have been the replacement of this incoherent diversity by a conceptual order. One might say that Montesquieu, exactly like Max Weber, wanted to proceed from the meaningless fact to an intelligible order. This attitude is precisely the one peculiar to the sociologist. [7] It means that a sociologist has to reach beyond the apparently diverse social forms and phenomena, which seem to be alien to one another, to reveal the unity in diversity in order to prove that all the diverse manifestations refer to the one and the same reality. In the same way, all the similar social events and phenomena have their origin in a similar sequence of analogous causes. Here is a passage from the observations on the causes of the rise and fall of the Romans: It is not fortune that rules the world. We can ask the Romans, who had a constant series of success when they followed a certain plan, and an uninterrupted sequence of disasters when they followed another. There are general causes, whether moral or physical ....which operate in every monarchy, to bring about its rise, its duration and its fall. All accidents are subject to these causes, and if the outcome of a single battle, i.e. a particular cause, was the ruin of a state, there was a general cause which decreed that that state was destined to perish through a single battle. In short, the main impulse carries all the particular accidents along with it. [8] The Holy Quran explains that nations and societies qua nations and societies (not just individuals living in societies) have common laws and principles that govern their rise and fall in accordance with certain historical process. The concept of a common fate and collective destiny implies the existence of certain definite laws governing the society. About the tribe of Bani Israel, the Quran says:

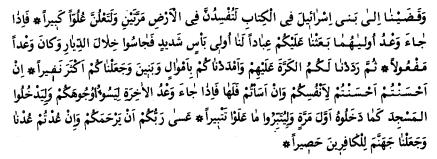

And We decreed for the Children of Israel in the scriptures: You varily will work corruption in the earth twice, and you will become great tyrants. So when the time for the first of the two came We roused against you slaves of Ours of great might who ravaged [your] country, and it was a threat performed.' [After you had regretted your sins and became pious again] Then we gave once again your turn against them, and We aided you with wealth and children and mode you more in soldiery. [saying] If ye do good, ye do good for your own souls, and if ye do evil, it is for them. (i.e. Our laws and customs are fixed and constant, it is by this covenant that people are bestowed with power, might, honour and constancy or subjected to humiliation and abjectness). So when the time for the second [of the judgements] came, because of your acts of tyranny and despotism, We aroused against you others [of Our slaves] to ravage you, and to enter the temple even as they entered it the first time, and to lay waste all that they conquered with an utter wasting. It may be that your Lord will have mercy on you[if ye mend your ways], but if you repeat [the crime] We shall repeat [the punishment], and We have appointed hell a dungeon for the disbelievers. (17:4‑8) The last sentence, i.e. "But if you repeat [ the crime] We shall repeat [the punishment]" shows that the Quran is addressing all the people of the tribe and not an individual. It also implies that all the societies are governed by a universal law. Part 6: Determinism or Freedom One of the fundamental problems discussed by philosophers, particularly in the last century, is the problem of determinism and freedom of individual as against society, or, in other words, determinism and freedom of the individual spirit vis‑a‑vis the social spirit. If we accept the first theory regarding the nature of society, and consider social structure to be merely a hypostatized notion, and believe in the absolute independence of the individual, then there will be no place for the idea of social determinism. Because, there will be no power or force except that of the individuals, and no social force that may rule over the individual. Hence, in this theory, there is no room for the idea of social determinism. If there is any compulsion or determinism it is of the individual and operates through the individuals. The society has no role in this matter. Hence, there can be no social determinism as emphasized by the advocates of social determinism. In the same way, if we accept the fourth theory, and consider the individual and individual's personality as a raw material or an empty pot, then the entire human personality of the individual, his intellect, and his free will would be reduced to nothing but an expression of the collective intelligence and the collective will, which manifest themselves, as an illusion, in the form of an individual to realize their own social ends. Accordingly, if we accept the idea of the absolute essentiality and primariness of the society, there will be no place left for the idea of the freedom and choice of the individual. Emile Durkheim, the famous French sociologist, emphasizes the importance of society to the extent of saying that social matters (in fact all the human matters, as against the biological and animal urges and needs, like eating and sleeping) are the products of society, not the products of individual thought and will, and have three characteristics: they are external, compulsive, and general. They are considered to be external, because they are alien to individual existence and are imposed from without upon the individual by society. They existed before the individual came into existence and the individual accepted them under the‑influence of society. Acceptance of the moral, social, and religious traditions, customs, and values by the individual comes under this category. They are compulsive, because they impose themselves upon the individual and mould the individual's conscience, feelings, thoughts, and preferences according to their own standards. Because of being compulsive, they are necessarily general and universal. However, if we accept the third theory and consider both the individual and the society as fundamental entities‑although admitting the power of the society as dominating that of the individual‑it does not necessitate any compulsion or determinism for the individual either in human or social affairs. Durkheimian determinism arises due to the failure to recognize the essential nature of the human being. Man's nature gives him a kind of freedom and liberty that empower him to revolt against social compulsions. On this basis, we may say that there is an intermediary relationship between the individual and the society that lies between the extremes of absolute freedom and absolute compulsion (amr bayn al‑'amrayn). Although the Holy Quran attributes character, personality, reality, power, life, death, consciousness, obedience, and disobedience to society, it also explicitly recognizes the possibility of violation of social law by an individual. The Quran in this matter relies on what is termed as the (Fitrat Allah)‘Divine nature’. In Surat al Nisa ; the verse 97 refers to a group of people who called themselves "mustad'afun" (the oppressed and the weak) in the society of Mecca, and took shelter in their `weakness and being oppressed' as an excuse for shirking their natural responsibilities. In fact, they considered themselves helpless as against the social compulsion and pressures. The Quran says that their excuse cannot be condoned on any ground, because at least they were free to migrate from the Meccan society to another one better suited for the fulfilment of their aspirations. Elsewhere it states:

O believers! You have‑ charge of your own souls. He who goes astray cannot injure you if you are rightly guided.(5:105) The famous verse (7:172) regarding human nature states that man is bound by the Divine covenant to believe in monotheism (tawhid), and it has been made inherent in human nature. The Quran says further that it is ordained in this way so that people should not say on the Day of Judgement that "our fathers were idolaters and we did not have any other alternative except helplessly adhering to the faith of our forefathers." (7:1709 With such a nature gifted to man by God, there is no compulsion to accept any faith contrary to the Divine will and to human nature itself. The teachings of the Quran are entirely based upon the notion of human responsibility‑man is responsible for himself and for society. The dictum: al‑'amr bil ma`ruf wa al‑nahy `an al‑munkar (commanding others to do what is commanded by God and forbidding them from that which is prohibited by Him), is a command to the individual to revolt against social corruption and destructiveness. This is the Quranic code of conduct prescribed for the individual to save society from chaos, disorder, and destruction. Tales and stories embodied in the text of the Quran deal mostly with the theme of the individual's revolt against a corrupt social order. The stories of Noah, Abraham, Moses, Jesus, Prophet Muhammad, the Companions of the Cave (Ashab al-Kahf), the believer of the tribe of the Pharaoh, etc. deal with the same theme. The notion of social determinism is rooted in the misconception that society in its real composition needs complete merger of its constituent parts into one another and dissolution of their plurality into the unity of the `whole'. This process is considered to be responsible for the emergence of a new reality. Either one has to accept that the personality, freedom, and independence of the individual are real, and so negate the reality of society and social structure (as in the case of the first and the second theories regarding the nature of society and the individual), or the reality of society is to be affirmed at the cost of the individual and his freedom and independence (as in the case of Durkheim's theory). A reconciliation between these two opposite viewpoints is impossible. As all the conjectures and arguments of sociology support the supremacy of society, the opposite view is necessarily rejected. In fact, from a philosophical point of view, all forms of syntheses cannot be regarded similar. On the lower levels of nature, i.e. minerals and inorganic substances, which in philosophical terms are governed by a `simple force,' and as interpreted by the philosophers, act according to one and the same law, are synthesized in a way that they completely merge into one another and lose their individuality in the whole. For example, in the composition of water, two atoms of Hydrogen and one atom of Oxygen are merged together, and both lose their individual properties. But at the higher level of synthesis, the parts usually retain a relative independence with respect to the whole. A kind of plurality in unity and unity in plurality manifests itself at higher levels of existence. As we see in man, despite his unity, a unique plurality is manifested. Not only his lower faculties and powers preserve their plurality to some extent, but, at the same time, there is also a kind of continuous inherent opposition and conflict between his internal powers. Society is the strangest natural phenomenon in which all its constituent parts retain their individual independence to a maximum possible degree. Hence, from this point of view, we have to accept that human beings, who are the constituent parts of a society in intellectual and volitional activity, retain their individual freedom, and, therefore, their individual existence precedes their social existence. In addition to this fact, in the synthesis at the higher levels of nature, the generic character of the parts is preserved. The individual human being or the individual spirit is not determined by the social spirit; it rather preserves its right to think and act freely. Part 7: Social Divisions and Polarization Although society has a kind of unity, it is divided from within into different groups, strata and classes, which are occasionally opposite to one another. If not all, some of societies are divided into different and occasionally conflicting poles despite their apparent unity. Thus, in the words of Muslim philosophers, a specific type of `unity in plurality and plurality in unity' governs societies. In earlier chapters, while discussing the nature of the unity of society, we have elaborated what type of unity it is. Now we shall discuss the nature of its inherent plurality. There are two well‑known theories with regard to this problem. The first is the philosophy of historical materialism and dialectical contradictions. This theory, which would be discussed in detail later, is based upon the origin of private property. The societies in which the conception of private property does not exist are basically unipolar, such as the primitive communist societies or those communist societies which are likely to be formed in the future. A society in which the right to private property. exists is, of necessity, bipolar: Hence, society is either unipolar or bipolar. There is no third alternative possible. In bipolar societies, human beings are divided into two groups, viz. the exploiters and the exploited. Except these two opposite camps, i.e. the group of the rulers and the group of the ruled, any third group does not exist. All the social modes, such as philosophy, morality, religion, and art, may also be divided according to the class character of the two groups. There are, therefore, two types of philosophy, morality, religion, etc., each of which bears the specific economic class character of each group. Hypothetically, if there were only one philosophy, one religion, and one morality prevalent in a society, it too represents the character of any one of these two classes and is imposed on the other. But it is impossible to imagine the existence of a philosophy, art, religion or morality without having a character independent of the economic structure of society. According to the other theory, the unipolar or multipolar characteristic of society has nothing to do with the principle of private ownership. The social, ideological, cultural, and racial factors, too, are responsible for giving rise to multipolar societies. The cultural and ideological factors, in particular, play the basic role; they are not only capable of producing bipolar or multipolar societies‑with occasionally contradictory poles‑but can also create a unipolar society without necessarily abolishing the institution of private ownership. Now we have to discuss the view of the Quran regarding the plurality of society. Does the Quran affirm or negate social plurality? And if it affirms, what is its point of view about the polarization of society? Does the Quran affirm the bipol4rization of society on the basis of ownership and exploitation, or does it forward some other view? The best or at least a good method for determining the Quranic point of view seems to be that we should first of all extract the social terminology used in the Quran. In the light of the nature and meaning of the Quranic idiom we can infer the position of the Quran concerning this matter. The social terminology used in the Quran is of two types: some of the words are related with a particular social phenomenon such as, millah (community), shari `ah (Divine Law), shir`ah (custom), minhaj (method), sunnah (tradition), and the like. These terms are not relevant to the present discussion. But a number of terms which refer to all or some human groups may be taken into account for discovering the Quranic viewpoint. These words can reveal the point of view of the Quran. Such terms as: qawm (folk), ummah (community), nas (mankind), shu`ub (peoples), qaba'il (tribes), rasul (messenger, apostle), nabi (prophet), imam (leader), wali (guardian), mu'min (believer), kafir (unbeliever), munafiq (dissenter or hypocrite), mushrik (polytheist), mudhabdhab (hesitant), muhajir (emigrant), mujahid (warrior), sadiq (truthful), shahid (witness), muttaqi (pious), salih (righteous), muslih (reformer), mufsid (corrupter), amir bil ma'ruf (one who orders to obey God's command), nahi `an al‑munkar (one who forbids indecent or illegitimate deeds), `alim (learned), nasih (admonishes), zalim (cruel, oppressive, unjust), khalifah (deputy), rabbani (Divine), rabbi (rabbi), kahin (priest), ruhban (monks), ahbar (Jewish scribes), jabbar (tyrant), `ali (sublime), mustali (superior), mustakbir (tyrant, proud), mustad`af (tyrannized, oppressed), musrif (lavish, prodigal), mutraf (affluent), taghut (idols), mala ` (chieftains), muluk (kings), ghani (rich), faqir (poor, needy), mamluk (the ruled), malik (owner, master), hurr (free, liberated), `abd (slave, servant), rabb (master, lord), etc. Furthermore, there are other words which are apparently similar to these words, such as: musalli (one who prays), mukhlis (sincere, devoted), sadiq (loyal, true), munfiq (charitable), mustaghfir (one who asks for God's forgiveness), ta'ib (penitent), abid (adorer), hamid (one who praises), etc. But these words have been used only for the purpose of describing kinds of behaviour and not to refer to certain social groups, poles, or classes. It is essential to study the connotation and meaning of the verses in which the terms referred to earlier are used, in particular the words related to social orientations. It is also to be seen whether the above mentioned terms can be divided into two distinct groups. And supposing that these terms refer to two distinct groups, it should be determined who are their referents; for example, can all of them be classified in two groups of believers and unbelievers, according to a classification based on religious belief, or into two groups of the rich and the poor according to their economic position? In other words, it is to be analysed whether these divisions are ultimately based on any one primary classification, and whether or not all the other sub‑divisions are essentially secondary and relative. If there is only one principle of division, it has to be determined. Some people claim that the Quranic view suggests a bipolar society. They say: according to the Quran, society is divided into two classes: one is the ruling, dominating, and exploiting class, and the other consists of the ruled, exploited, and subjugated people. The ruling class consists of those whom the Quran calls `mustakbirun', i.e. the arrogant oppressors and exploiters. The subjugated class is of those who are called by the Quran `mustad'afun' (the weakened). All other divisions, such as mu'min (believer) and kafir (unbeliever), muwahhid (monotheist) and mushrik (polytheist), salih (righteous) and fasid (corrupt) are secondary in nature. It means that it is tyranny and exploitation that leads to infidelity, idolatry, hypocrisy and other such evils, whereas, on the other hand, subjugation to oppression and exploitation leads towards iman (faith), hijrah (migration), jihad (struggle), salih (righteousness), islah (reform) and other such qualities. In other words, all such things which are regarded by the Quran as deviation and aberration in religion, morality, and deeds are rooted in the practice of exploitation and the economic privileges of a class. Similarly, the source and root of the attitudes and acts morally, religiously, and practically approved and emphasized by the Quran, lie in the condition of being exploited. Human consciousness is naturally determined by the material conditions of life. Without changing the material life of a people, it is not possible to bring about any change in their spiritual, moral and psychic life. According to this viewpoint, the Quran perceives social conflicts as basically class‑conflicts. It means that the Quran gives essential priority to social and economic struggle over moral struggle. According to this interpretation, in the Quran, infidels, hypocrites, idolaters, the morally corrupt and the tyrants arise from among the groups whom the Quran names as mutraf (the affluent), musrif (extravagant and wasteful), mala' (ruling clique), muluk (kings), mustakbir (arrogant) and so on. It is not possible for these groups to arise from among the opposite class. In the same way, they say, the prophets (anbiya'), messengers (mursalun), leaders (a'immah), upholders of truth (siddiqun), martyrs (shuhada'), warriors (mujahidun), emigrants (muhajirun) and believers (muminun) emerge from among the class of the oppressed and the weak. It is not possible that they may arise from the opposite class. So it is mainly istihbar (tyranny and arrogance) or istid`af (weakness, or condition of being oppressed) that mould and direct the social consciousness of the people. All the other social modes are products and manifestations of the struggle between the exploiters and the exploited, and the oppressors and the oppressed. According to this viewpoint, the Quran not only considers the two above‑mentioned groups of people as manifestation and expression of the division of society into two classes of the mustakbirun and the mustad'afun, but it also divides human attributes and dispositions into two sets. Truthfulness, forgiveness, sincerity, service, insight, vision, compassion, mercy, pity, generosity, humility, sympathy, nobility, sacrifice, fear of God, etc. constitute one set of positive values; on the other hand, falsehood, treachery, debauchery, hypocrisy, sensuality, cruelty, callousness, stupidity, avarice and pride etc. constitute another set of values, which are negative. The first set of attributes are ascribed to the oppressed class and the second set is considered to characterize the oppressors. Hence, they say, oppression and subjugation not only give rise to opposite groups, but they are also the fountainheads of conflicting moral qualities and habits. The position of a class either as oppressor or oppressed is the basis and foundation not only of all human attitudes, loyalties, and preferences, but also of all cultural and social phenomena and manifestations. The morality, philosophy, art, literature, and religion originating in the class of oppressors always manifest and represent its character and social attitude. All of them support and justify the status quo, and cause stagnation and decadence by arresting social progress. On the other hand, the philosophy, art, literature, and religion originating from the class of the oppressed are dynamic and revolutionary, and generate new awareness. The class of the oppressors, i.e. the mustakabirun, because of its hegemony over social privileges, is obscurantist, traditionalist, and seeks shelter under the shadow of conservatism; whereas the class of the oppressed is endowed with vision, and is anti-traditionalist, progressive, zealous, active, and is always in the vanguard of revolution. In brief, according to the advocates of this theory, the Quran affirms the view that it is actually the economic structure of a society which makes a man, determines his group‑identity and his attitudes, and lays down the foundation of his thinking, morality, religion, and ideology. They quote a number of verses from the Quran to show that what they teach is, on the whole, based upon the Quran. According to this view, commitment to a particular class is the measure and test of all things. All the beliefs are to be evaluated by this standard. The claims and assertions of a believer, a reformer, and even a prophet or a spiritual leader, can be confirmed or rejected only through this test. This theory is in fact a materialistic interpretation of both man and society. No doubt the Quran gives a special importance to the social allegiances of individuals, but does it mean that the Quran interprets all distinctions and classifications on the basis of social classes? In my view such an interpretation of society, man, and the world is not consistent with the Islamic world‑view. It is a conclusion drawn from a superficial study of the problems discussed in the Quran. However, since we shall discuss this matter fully in a later chapter dealing with history under the title "Is History Materialistic in Nature?" I shall abstain from further elaboration at this point.

Footnotes: [7]. Raymond Aron, Main Currents in Sociological Thought, vol. I, p. 14. [8]. Ibid. |