|

|

Sociology of the Qur'an Murtadha Mutahhari - 1 - Part 1: Introduction The outlook of a school of thought regarding society and history and its specific approach to them, plays a decisive role in its ideology. From this point of view, it is essential, in the context of Islamic world outlook, to throw light on the Islamic approach to society and history. It is evident that Islam is neither a theory of society nor a philosophy of history. In the sacred Book of Islam, no social or historical problem is dealt with in the technical jargon of sociology and philosophy of history. In the same way no other problem, ethical, legal or philosophical, is discussed in the Quran, either in the current terms or according to the traditional classification of sciences. However, these and other problems related with various sciences can be deduced from the Book. Islamic thinking on society and history, because of its special importance, is a topic that deserves to be studied and investigated properly, and, like its many other teachings, reveals Islam's profoundness in dealing with various issues. Since the problems that deal with society and history are closely related, and since we wish to discuss them briefly, it was apt to discuss them together in a single book. However, we shall discuss the problem related to society and history only to the extent that would help in understanding Islamic ideology. We shall begin with society and then proceed to discuss history. Following are some of the questions that can be raised about society: 1. What is society? 2. Is man by nature social and gregarious? 3. Is it true that the individual is primary and society is secondary, or is the truth contrary to it, that is, society is primary and individual is secondary in importance? Or is there any third possible approach? 4. The relationship between society and tradition. 5. Whether the individual is free or if he is determined by society and the social structure? 6. In what institutions, poles, and groups is society classifiable according to its primary divisions? 7. Whether human societies are absolutely of the same nature and essence, their differences being similar to the differences among members of the same species? Or if they vary according to geographic variations, temporal and spatial conditions, and levels of development of their culture and civilization, assuming different forms and essences with each calling for a separate sociology based upon its particular ideology? In other words, is a single system of sociology, ethics, and ideology applicable to all humanity, in the same way as a single system of medicine and laws of physiology applies to all human beings regardless of their geographic, racial and historical variations? Does every society, according to its regional, cultural and historical background, require a special sociology and affirm a particular ideology? 8. Are human societies, which from the dawn of history up to the present day have been diversified and grown independent of one another, with a kind of pluralism governing them (at least in an individual if not in a generic sense), moving from plurality and diversity towards attainment of unity and homogeneity? Does the future of humanity lie in attaining one society, one culture and one civilization, and whether at the end its plurality will be replaced by a stage of homogeneity in which all its contradictions and conflicts would be overcome and resolved? Or, contrarily, is humanity eternally condemned to multiplicity of culture and ideology, and to a pluralism that reinforces the social identity of its particular, units? In our view, these are the relevant problems which need to be discussed from the Islamic point of view, so that these issues are brought to light and put. in a proper perspective. We propose to deal briefly with these issues one by one. Part 2: What is Society? A society consists of groups of human beings who are linked together by means of specific systems and customs, rites and laws, and have a collective social existence. Collective life is that in which groups of people live together in a particular region, and share the same climate and similar foodstuffs. Trees of a garden also `live' together and share the same climate and the same kind of nourishment. In the same manner, gazelles of a herd also graze together, and migrate together from place to place. But neither trees nor gazelles can be said to have a social life, as they do not form a society. Human life is social in the sense that it is essentially gregarious. On the one hand human needs, benefits, satisfactions, work, and activity are social in essence, and the social system cannot be maintained but through division of labour, division of profits and a shared common satisfaction of needs within a particular set of traditions and systems. On the other hand, specific ideas and ideals, temperaments, and habits govern human beings in general, giving them a sense of unity and integration. In other words, society represents a group of human beings, who, under the compulsion of a series of requirements and under the influence of a set of beliefs, ideals and goals, are amalgamated with one another and are immersed in a continuum of collective life. The common social interests, and particular ties of human life unite human beings together, giving to every individual a sense of unity similar to that experienced by a group of people travelling together in an automobile or an aeroplane or a boat, heading towards the same destination, and sharing together the common hope of reaching the destination safely, the dangers of the way, and a common fate. How beautifully the Prophet of Islam (S) has described the philosophy of `enjoining right conduct and forbidding indecency' (al‑'amr bil ma'ruf wa nahy `an al‑munkar) by means of the following parable: A group of people board a ship that sets sail on the sea tearing apart the waves. Every one of them has a seat reserved for him. One of the travellers claiming that the seat occupied by him belonged to none other than him, starts making a hole under his seat with a sharp tool. Unless all the travellers immediately hold his hand and make him desist from doing so, they would risk drowning not only themselves but would also fail to save the poor wretch from being drowned. Part 3: Is Man Social by Nature? The problem regarding the factors responsible for the emergence of social life in human beings, has‑been raised from the ancient times. Is man born with the instinct of gregariousness, i.e. whether he was naturally created as a part of a whole, with an urge in his nature to be united with the whole; or if he was not created as a gregarious being, but external compulsions and determinism imposed upon him a collective life? In other words, is he by nature inclined to live freely, and is disposed not to accept any kind of obligations and restrictions which have been imposed upon him, although they may be essential for social life? Has he in fact learnt from experience that no one is able to continue one's life in isolation, and so he has been forced to surrender to limitations imposed by social life? Or, although he is not gregarious by nature, the factor that persuaded him to accept social existence was not compulsion, or at least compulsion had not been the sole factor? Or, was it by the ruling of his reason and through his faculty of calculation that he arrived at the conclusion that only through cooperation and social life could he better enjoy the gifts of nature, and, therefore, he chose to live in company with other human beings? Accordingly, the problem can be posed in three ways: (i) Man is social by nature; (ii) he is social by compulsion; (iii) he is social by his own choice. According to the first theory, man's social life is similar to the partnership of a man and a woman in married life; each of the partners was created as a part of a whole, and, by nature, yearns to be united with the whole. According to the second theory, social life is like cooperation, such as a pact between two countries which are singly unable to defend themselves against a common enemy, and are forced to work out an agreement of co‑operation and collaboration. According to the third theory, social life is similar to the partnership of two capitalists, which gives rise to a commercial, agricultural or industrial company aiming at attainment of greater profits. On the basis of the first theory, the main factor is inherent in man's own nature itself. On the basis of the second theory, it is something external to man's essence and independent of it. And according to the third theory, the main factor responsible for social life is man's intellectual and calculating faculty. According to the first view, sociability is a general and universal goal which man naturally aspires to attain. According to the second theory, sociability is a casual and accidental phenomenon, a secondary and not a primary objective. According to the third theory, sociability is the result of man's faculty of reasoning and calculation. It may be said on the basis of the study of the Quranic verses that sociability is inherent in the very nature and creation of man. In the Surah al Hujurat the Quran says:

O mankind! We have created you male and female, and have made you nations and tribes, that you may know one another [not that on account of this you may boast of being superior to others]. Certainly, the noblest of you, in the sight of Allah, is the most God‑fearing among you ....(49:13) In this verse, besides an ethical precept, there is an implication which indicates the philosophy of social existence of man, according to which mankind is so created that it always lives in the form of groups, nations and tribes, and an individual is known through his relation to his respective nation and tribe‑an identity which is an integral part of social existence. If these relations‑which, in one way, are the cause of commonness and association between individual men, and, in the other way, are the cause of their separation and dissociation‑did not exist, it would have been impossible to distinguish one man from another. As a consequence, social life, which is the basis of relationships of human beings with one another, would not have come into existence, These and similar other factors in social life, such as differences in features, colour, and physique, provide the ground for specific marks of distinction of an individual and impart individuality to persons. Had all the individuals been of the same colour, features, and physique, and had they not been governed by different types of relationships and associations, they would have been like the standardized products of a factory, identical to one another, and consequently could not be distinguished from one another. It would have ultimately resulted in the negation of social life, which is based upon relations and exchange of ideas, labour,. and commodities. Hence, association of individuals with tribes and groups has a natural purpose. The individual differences among human beings serve as an essential condition of social life. It must not, however, be used as a pretext for prejudice and pride; for superiority is supposed to lie in human nobility and an individual's piety. In verse 54 of Surah al‑Furqan, the Quran states:

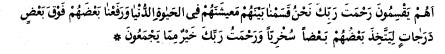

And He it is who hath created man from water, and hath appointed for him kindred by blood [relationships by birth] and kindred by marriage [acquired relationships]. (25:54) This verse reveals the purpose of birth‑relationship and marriage relationship, which together bind individuals with each other, as underlying the design of creation. It is through these relationships that individuals are distinguished from one another. In Surat al‑Zukhruf, verse 32, it is stated:

Is it they who apportion their Lord's mercy? We have appointed among them their livelihood in the life of the world and raised some of them above others in rank, that some of them may tape labour from others, and the mercy of thy Lord is better than [the wealth] that they amass. (43:32) While discussing the conception of tawhid (Divine Unity), in the part dealing with the world outlook of tawhid, I have dealt with the meaning of this verse.' Here I will give just the substance of the verse. Human beings have not been created alike in respect of their talents and dispositions. Had they been created so, everyone would have possessed the same qualities and all would have lacked diversity of talents. Naturally, as a consequence, none would have required the services of others, thus making mutual co‑operation and mutual obligations meaningless. God has created man in diversity with different spiritual, physical, and intellectual aptitudes, dispositions, and inclinations. He has given some people special abilities, and has imparted superiority to some over others in certain talents. By means of this, He has made all human beings intrinsically needful of others and inclined to associate with others. Thus He has laid down the foundation of collective and social life. The above‑mentioned verse also asserts that social existence is not merely a conventional, or selective or a compulsive affair, but a natural one.

Footnotes: [1]. Jahan bini‑ye tawhidi ("The World‑view of Tawhid") is another of Martyr Murtada Mutahhari's books which also, like the present work, is a part of Muqaddameh a bar jahan bini‑ye Islami ("Introduction to the World Outlook of Islam"). (Tr. ) |